How One Woman With Down Syndrome May Help Redefine Alzheimer’s Resilience

In an extraordinary case that’s turning heads in Alzheimer’s research, a woman with Down syndrome has defied all expectations—and potentially changed how scientists understand the disease. Despite showing advanced signs of Alzheimer’s disease in her brain, she remained cognitively stable into her 60s, a decade beyond when most people with Down syndrome begin to show symptoms of dementia.

Her story, published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, is a testament to the power of scientific curiosity—and personal generosity. The woman, a participant in the Alzheimer Biomarker Consortium–Down Syndrome study led by Dr. Elizabeth Head at the University of California, Irvine, had chosen to donate her brain to science. What researchers found after her death was nothing short of astonishing.

“It was remarkable to see a person escape the learning and memory changes yet still have brain changes,” said Dr. Head in an interview with Newsweek.

A Brain Full of Pathology, A Life Full of Clarity

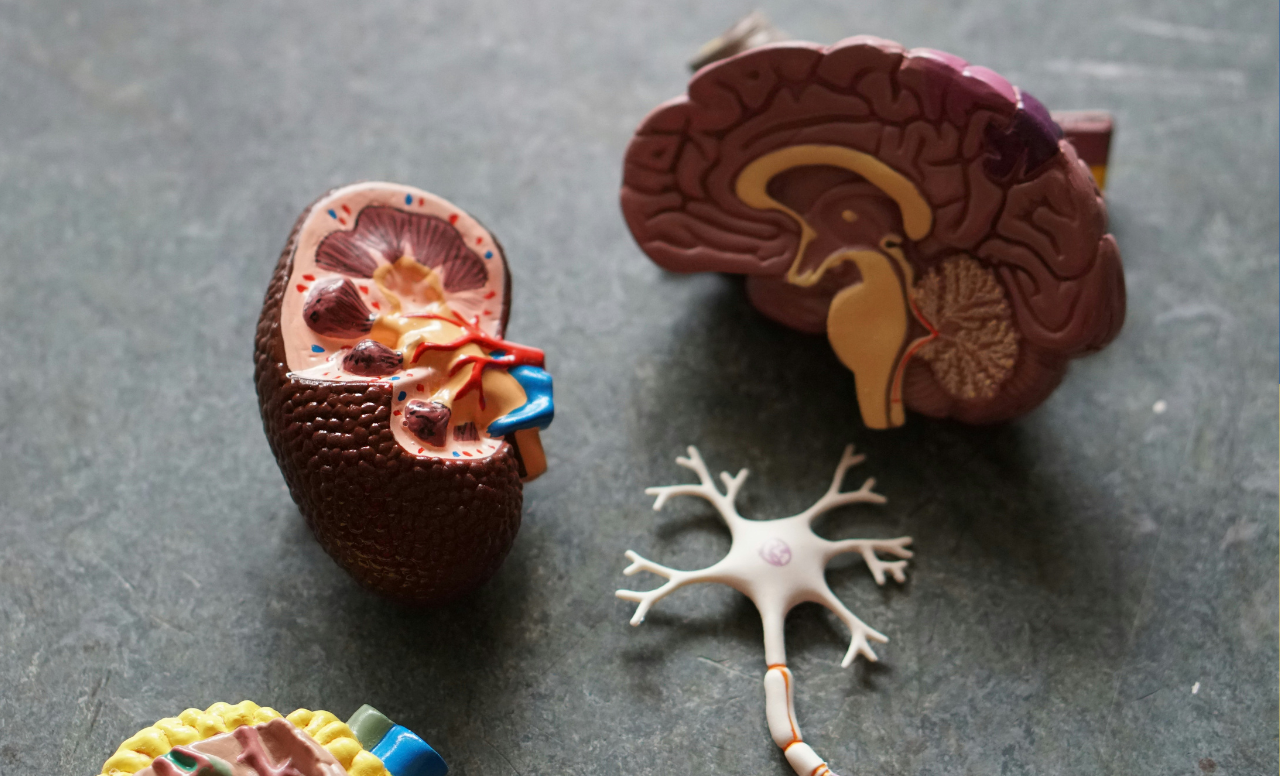

The woman’s brain was examined at the University of Pittsburgh using a high-resolution 7 Tesla MRI scanner. The imaging revealed extensive Alzheimer’s pathology—amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles—features that usually lead to significant cognitive decline. But during her lifetime, this woman exhibited no signs of dementia.

“Before she passed away, all the clinical assessments in our years of studying her indicated that she was cognitively stable,” said Jr-Jiun Liou, the study’s lead postdoctoral researcher.

This case poses a major question: How can someone with the full biological signs of Alzheimer’s remain mentally sharp?

Clues to Cognitive Resilience

The researchers propose that the woman’s resilience may be explained by one or more protective factors:

- Genetic variations that helped her brain resist damage.

- A high level of education, which may have provided “cognitive reserve”—a buffer against memory loss.

- An enriched lifestyle that kept her brain active and engaged.

If scientists can identify the exact mechanisms behind this resistance, it could lead to new treatments and early interventions—not only for people with Down syndrome, but for the broader population at risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

“This case study gives us real hope to unlock approaches to deliver this type of resilience for all those with or at risk for cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease,” Head said.

A Call for More Inclusive Research

This discovery is also raising important questions about who gets included in Alzheimer’s clinical trials. Currently, individuals with Down syndrome are often excluded from therapeutic studies because of their “atypical” pathology. But this case challenges that logic.

“Our study highlights how even one person can have a significant impact on helping us find a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease,” said Head.

Head and Liou are now advocating for broader inclusion in Alzheimer’s trials, which could reveal additional subgroups of people who, like this woman, demonstrate an extraordinary resilience to neurodegeneration.

Why This Matters

People with Down syndrome are at significantly higher risk for Alzheimer’s. By age 40, most will have brain pathology consistent with the disease, and by their mid-50s, about 90% will show signs of cognitive impairment. This woman’s case provides a beacon of hope that decline isn’t inevitable—and may even be preventable.

As researchers analyze her brain in more depth, the hope is that this unique story becomes the foundation for transformative insights into diagnosis, prevention, and treatment for all forms of Alzheimer’s.

“We have made wonderful progress and feel we are on the precipice of even more learning that will have huge impact for public health if we continue to invest in research,” said Head.

References:

- Liou, J.-J., et al. (2025). A neuropathology case report of a woman with Down syndrome who remained cognitively stable: Implications for resilience to neuropathology. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 21. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.14479

- Afshar, M. F. (2025, March 4). Woman Donated Her Brain to Science—Alzheimer’s Experts Shocked by Discovery. Newsweek

- Alzheimer Biomarker Consortium – Down Syndrome (ABC-DS). NIH Study Overview